How 'First We Eat' Explores the Importance of Food Sovereignty and Security in the Modern Era

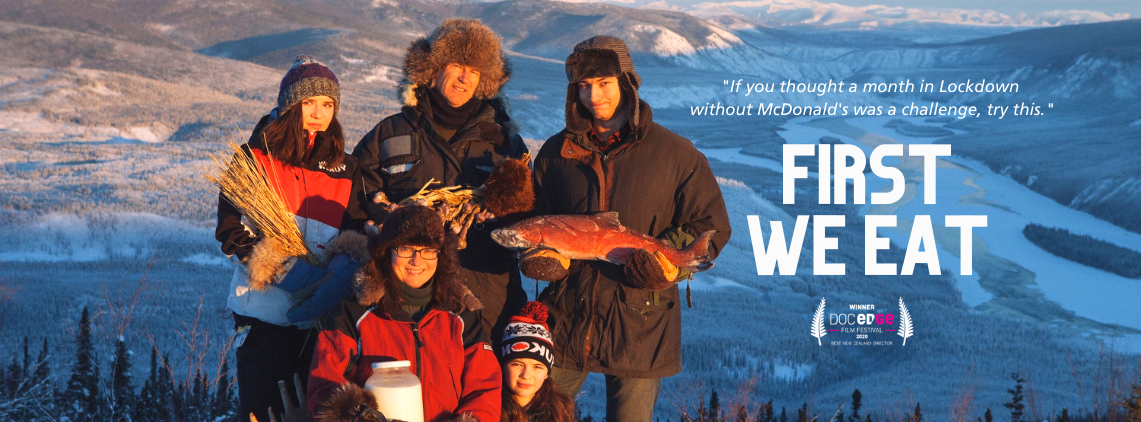

First We Eat is Suzanne Crocker’s award-winning 2020 documentary about food, family, sustainability and, ultimately, survival. The Canadian doctor-turned-filmmaker lives with her husband and three children in Dawson City in the Canadian territory of Yukon. It is a city inseparably linked to the Klondike Gold Rush when, in 1898, the traditional homeland and fishing grounds of the First Nation Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in people was occupied by 40,000 prospectors. These days, it is home to just 1500 resilient residents, who face annual winter temperatures of -40°C and three months of near total darkness. When a landslide cuts off the road to Dawson, the supermarkets start running out of food within just 48 hours. In this small remote community just 300km from the Arctic Circle, 97% of food is trucked in on the single road that connects the city to the South. Imported fresh produce is expensive, has a huge carbon footprint, and, by the time it reaches Dawson, is depleted of much of its nutritional value, owing to the time spent in storage and transit. Crocker’s response to this wake-up call about the very real threat of food scarcity in her hometown is to set herself the challenge of feeding her family 100% local food for one year. Everything they consume during this time must be grown, gathered, hunted or fished around Dawson.

This is not the first time the Crocker family have been subjected to one of their mother’s unusual ideas. In 2014, the family spent nine months living off-grid in a cabin in the wilderness sans the modern technology and indoor plumbing in Suzanne’s debut documentary All the Time in the World. However, while it is evident in First We Eat that her three teenagers are used to being part of their mother’s eccentric pursuits, there is an authenticity to their comical and not infrequent outbursts of disgust. Always at least willing to have a taste, in the end they do develop a grudging tolerance for the project but their vocal cravings for bagels and cheerios save the film from being overly proselytising.

Refreshingly, Suzanne is neither an expert cook nor gardener, and she considers herself a ‘blank page’, readily seeking the help and knowledge of her community. She turns to the expertise of local growers and farmers, and, in particular, to the wisdom of the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in, the First Nation inhabitants of the Yukon valley who, prior to colonisation, had been living off the land for thousands of years. Her mission is to know not just where every ingredient on her plate comes from but also to ‘know the people who helped put it there’. We learn alongside her about what goes on at the most northern dairy in North America, how to overwinter bees in temperatures of -40°C, the proper way to catch and prepare Chinook salmon and the surprisingly bounteous foraging potential of the boreal forest. The saying ‘it takes a village’ is appropriate as we watch the local community take it in turns to churn the family butter while joining in traditional dances at the town hall. The film is a true celebration of this hive of northern knowledge, and each producer and elder is given significant airtime to share their philosophy, techniques, and accomplishments. Having worked for the last few years for an organisation seeking to build a fair, sustainable local food system in Scotland, this, for me, was the most exciting element of the film. There is a lot to be learnt from Dawson’s local food heroes; their resilience, optimism and ingenuity in the face of extreme climate and topographical challenges is inspiring.

First We Eat also captures the disorderliness of food. In the age of Instagram, the food we see is so often aestheticized and sanitised, appearing, as if by magic, on a painstakingly food-styled plate. Here, this is emphatically not the case. Scenes of butchering animals aside (essential viewing for any meat eaters), eating local for a year is messy! As a reasonably tidy cook (with a willing washer-upper on hand), the chaos that abounds in the Crocker household made me feel anxious just to look at it. The amount of processing and storage space required for the 100% local diet is staggering. There is a moving moment when Suzanne, exhausted from the days culinary endeavours and surrounded by kitchen detritus on every inch of worktop, calls mournfully to her family to come and help clean up. Look out also for the scene where she boils mud until it slops all over the stovetop in a valiant attempt to procure salt from a mineral lick. The take-home from this aspect of the film is imperative. We need to stop expecting our food to be clean, colourful, and shiny, year-round. Even though, as a nation, we are now fairly unanimous in our dislike of plastic packaging, we have much further to go in our acceptance of mud, blood and mess when it comes to preparing and cooking the food we eat. We can ditch the glossy peppers and gleaming aubergines in February, buy some muddy root vegetables and get scrubbing. We can save our mess of peelings to make stock. In March, as the season of these winter roots draws to a close, we can sterilise our empty jars, fumigate our flats with vinegar, and get pickling and fermenting, reducing our reliance on foreign imports during what is known as the ‘hungry gap’ in the harvest calendar. In the Crocker kitchen, nothing is wasted, and there is plenty we can do to make sure the same is true in our own.

In our pandemic ravaged, post-Brexit world where climate chaos impacts harvests more severely with each passing year, empty supermarket shelves have become commonplace. Long supply chains are increasingly unstable and unsustainable, and panic-buying or stockpiling, an even more unsustainable solution. Now, more than ever, we should be considering where our food comes from. As the film confirms, the benefits of eating local are abundant: enabling us to reduce our carbon footprint, lessening the prospect of food insecurity, as well as increasing our self-sufficiency, not to mention boosting the food’s nutritional value. Crocker does not underplay the challenges of the project (which are many) but it is clear that it is also a fantastic springboard for creativity, innovation, and community building. Of course, we don’t all have the time, space, means and access to take it as far as the Crockers, and neither is the film suggesting we must. On the First We Eat website, there is a useful compilation of simple, doable ways you can eat more thoughtfully and sustainably before you start emptying the cupboards of supermarket snacks.

First We Eat is a powerful exploration of the meaning of food sovereignty and security, and a celebration of the joys of eating local, seasonal food. The sweeping, meditative shots of the pristine but threatened Yukon valley remind us of the unique remoteness of the location where the growing season is just 66 days. As several characters in the documentary point out, ‘if it can be done here, it can be done almost anywhere’, ‘it’ being source 100% of one’s food locally and ‘here’ being at the inhospitable latitude of 64° N, and a six hour drive from the nearest Starbucks. And it’s true. While we don’t all need to give up sugar, caffeine and salt and take up foraging, we can probably get our hands on, at the very least, some organic potatoes, onions and carrots grown close to where we live. That’s a cheap, nutritious and 100% local soup right there. The film derives its name from the beloved food writer M.F.K Fisher’s much quoted bon mot ‘First we eat, then we do everything else’. In actuality, First We Eat brings home just how much work has to be done first, in order for us to eat and how we have come to take this for granted. Suzanne Crocker invites us to engage actively, intimately and prudently with the food we eat and, to consider how much better it might taste if we do…

Miriam Cocker

Miriam is an Edinburgh-based freelance writer. After graduating, she spent a few years working in the organic fruit and veg business, gaining an expert knowledge of seasonality, local produce and sustainable food systems. After lifting one too many sacks of potatoes, she decided she would rather write about them instead.

Website : miricooks.wordpress.com

Instagram: miri_lucy